First off, I really appreciate the Record-Herald for running a story on my internship. That's the sort of thing that can only happen in a great small town like Indianola. As much fun as I am having here in DC, there are moments where I miss Indianola, and the article gave me another great connection back home.

My parents visited over the weekend, and I took them everywhere. You know, all the big things people have to see in DC. It was great, but we are all worn out. I had a list of things I intended to do tonight... writing this post is the only thing I will get through.

Also, DC Cab drivers can't find the Washington Monument unless you can give them the address. But, anyway...

This week, I'm looking forward to going to Philadelphia on Sunday. As long as I'm out here, I decided I would hop on a train to the birthplace of our nation. I'll see Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and make it a bit south to the SS United States and lay eyes on her before she ends up (hopefully not) being scrapped.

I'm making headway on the DCPS professional development plan I'm working on. Today was the most productive day I've had in a few days since all the pieces are starting to come together.

So, now, the Top 5 Best Air and Space Museum Artifacts Nobody Knows About.

This is just my top 5. There might be some artifacts still out there on display I don't know about. I figured everyone knows about Apollo 11, the Lunar Module, Spirit of St. Louis, etc. I put together a short list of significant but little-known artifacts people come across without knowing the significance of the artifact.

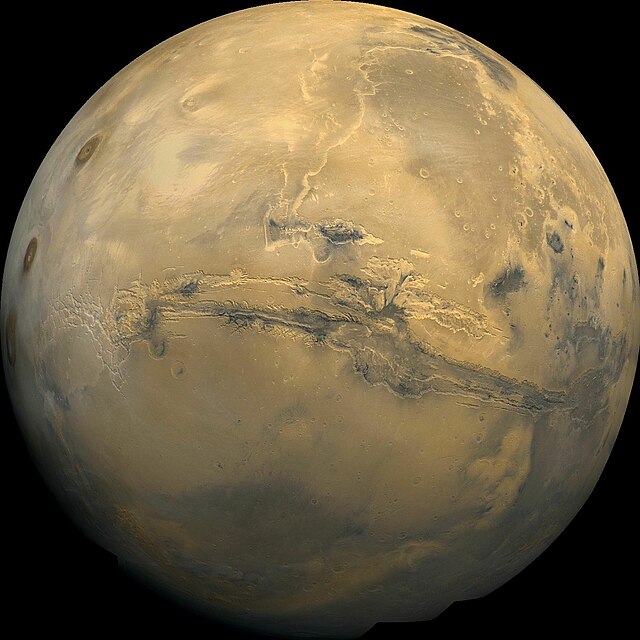

5. Percival Lowell's Mars Globe

Percival Lowell was an early-20th Century astronomer who studied Mars through telescopes. He saw lots of lines and ridges, and became convinced they were canals built by a highly-advanced civilization in order to channel water from Mars' poles to the rest of their drying planet.

From that description, you might have an image of Lowell as some turn-of-the-century Doc Brown, crazy hair and all. Lowell was no crackpot scientist, but was once regarded as the most brilliant man in Boston. In fact, although he didn't discover Pluto, he observed strange variations in the orbit of Neptune and determined they must be caused by some undiscovered planet. Pluto was eventually discovered near where Lowell said it would be.

This was probably a perfect example of someone having a preconceived notion and then fitting all the evidence into place to support that preconception. He grew up around canal builders, and had experience with the "alien world" of Japan. His life experiences and greatest desires convinced him that Martians were intelligent, and Mars was a perfect Utopia.

Sadly, that is not the case. What he actually observed were canyons. But those canyons were massive. See for yourself:

|

| Easy mistake. |

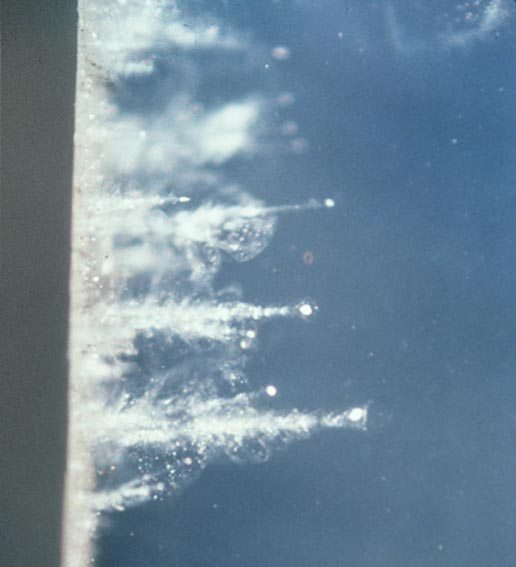

4. Stardust Probe

Given the time and resources, scientists will always find a way to prove (or disprove) their theories. It never fails.

At the museum, all of our satellites and probes are either replicas, engineering models, or backups. Not Stardust - this one is the real deal, to space and back.

Besides being awesome looking, scientists think comets may hold the building blocks to life itself. We were certain comets are made from rock and ice. But, like almost everywhere outside of Earth, had no hard evidence.

So, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Goddard Space Flight Center decided that wasn't right, and decided not to rely on the statistical probability that a comet will find it's way to Earth's surface eventually.

No, Ma'am. If something's out there, let's go out and get it!

The Stardust Probe was launched in 1999 to visit the comet Wild 2 (no, the comet was not named by an astronomer with an unhealthy obsession over westerns... It's pronounced Vilt Two, after Swiss astronomer Paul Wild, who discovered it in 1978).

To capture particles of the Wild 2, the tennis-racket-like arm sticking out from the top was filled with a material called Aerogel, the least-dense solid known to (and created by) man. It is 99.8% air. People even call it solid air. The aerogel trapped the particles of the comet without damaging or contaminating them.

|

| Grains of dust in the Aerogel collector |

After collecting the particles, the sample container was jettisoned on a path toward Earth, where it landed in the Utah desert.

Besides finding dust particles that were older than our sun, Stardust also found amino acids, the building blocks of DNA.

How about that?

3. "Kaputnik," The Vanguard TV-3

This was supposed to be America's first satellite in orbit. Instead, it was an embarrassment.

Everyone knows the story of the space race, and how the U.S. and Soviet Union were competing for every major milestone in space exploration. Project Vanguard and Sputnik were being developed in parallel.

The TV-3 was supposed to be launched atop a Vanguard rocket. There was one problem: The Vanguard didn't work.

On October 4th, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite. When the U.S. tried to launch TV-3 onboard a Vanguard on December 6th, the rocket rose 4 inches off the launch pad, collapsed, and exploded.

But here's the kicker: The TV-3 was designed to begin emitting a radio signal once it detached from the nose cone, which was only supposed to happen once it reached orbit. Unfortunately, the TV-3 didn't know the difference between Space and Earth. It was ejected from the Vanguard, landed in the nearby woods, and started emitting its radio signal from there.

The media called it a "Flopnik," "Stayputnik," and "Kaputnik."

All was not lost. Eventually, Explorer 1 became the first U.S. satellite, launched a few days later aboard a Jupiter-C rocket. A Vanguard would eventually launch TV-4, which is still in orbit to this day, and will be for at least another 180 years.

2. Apollo Sextant

Sextants have been used for navigation since at least 1750. You might be more familiar with models that look more like this:

Sextants are used for celestial navigation. By measuring the angle between two points - usually either the Sun (during the day) or Polaris (at night), one can do a bit of fancy math and figure out where you are.

One would think we had moved beyond such rudimentary measures by the Apollo era. Surely they used GPS, or some more fancy method of determining their position than what Captain Hook used.

This was not the case. Yes, Apollo had a gyroscope system that would keep track of every movement to help determine position, but this system had a tendency to become misaligned over time. The Apollo astronauts needed to do periodic checks with their sextant to determine their location in space.

Yes, the Apollo astronauts found their way to the Moon the same way John Paul Jones navigated his ship in the Revolutionary War - by taking sightings on stars.

And this was absolutely critical. During Apollo 13, an explosion aboard the space craft scattered so much debris around they could not tell the difference between the debris and the stars, making celestial navigation impossible. The best they could do was hope their guidance platform was correct... even when the math used to set the platform was performed while the astronauts were facing imminent death from a spacecraft that had just exploded.

Eventually, Apollo 13 was able to take a sighting on the Earth and the Sun. Not ideal, since stars are much more precise, but it worked.

Thank you, Sir Isaac Newton.

1. Mutch Memorial Station Plaque

Can you call something an artifact when it hasn't even been used for its intended purpose? OK, now that I've done the intro, go ahead and read the letter that accompanies the plaque that is displayed by the engineering model of the Mars Viking Lander.

Yes, we have something that will someday be an artifact. Until then, we have it under safekeeping. One day, NASA will call the Air and Space Museum to inform them that NASA is going to come get the plaque, and humans will take it to Mars and place it on the Viking Lander.

There's not much more I can say about that. This plaque is my favorite artifact that no one knows about.

No comments:

Post a Comment